Clothes are so readily available today – purchased cheaply through chain stores (though recent exposure of labour conditions and wages paid might make us think twice), at high-end designer boutiques, in op-shops or online – that it can be hard to imagine such short supplies that they need to be rationed. But in Australia, pressing shortages resulted in civilian clothes rationing spanning a six-year period between 1942 and 1948. Alongside it, a black market loomed.

Dwindling supplies of cloth and clothing were apparent in 1941. The subsequent rationing of clothing was put in place from May 1942, after which a coupon system was introduced to manage scarcity and ensure equitable distribution. But some still longed for garments now considered a luxury. Others were unwilling to wait months to purchase the clothing which was available. A black market in clothing, and the uncut cloth to make it, began to flourish Australia wide.

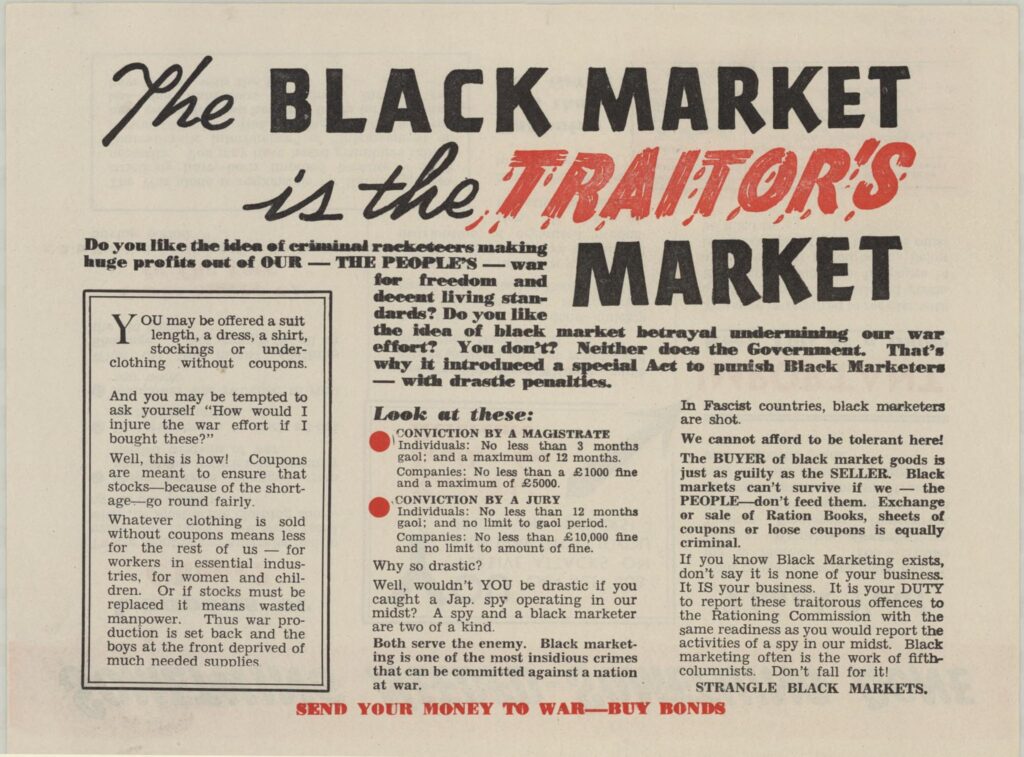

In 1943, the Australian Government published a leaflet titled The Black Market is the Traitor’s Market. It sent a clear message: black marketing was ‘one of the most insidious crimes that can be committed against a nation at war’ and buying black market goods not only injured the war effort but was an act of betrayal.

Clothing materials were stolen after leaving mills, in transit from wharfs or train stations, or in warehouses where they were stored prior to distribution. Those caught were arrested and charged. For the right price, clothing was sold without the required coupons – though this price was often severely inflated. Material used to make men’s suits were eagerly sought and made up by back-room tailors or sold by door-to-door agents.

But buying from a seller going house to house posed its own problems: those who purchased black-market goods were liable for a fine or gaol time. And for traders, the retribution was swift: by mid-1945 more than 760 prosecutions were recorded.

Normally-sensible tailors fell foul of black-market temptations, as did suburban housewives missing a range of goods and the freedom of choice. Yet the leaflet was clear: ‘The BUYER of black market goods is just as guilty as the SELLER’, and it roused Australians to ‘STRANGLE BLACK MARKETS.’

References

‘Big Black Market “Ring” Gets Huge Rake-Off from Clothing’, Sun, 31 May 1945, 3.

‘Blackmarket in Clothing’, Morning Bulletin, 6 June 1945, 6.

‘Brisbane’s Black-Market’, Smith’s Weekly, 22 December 1945, 1.

‘Huge Queensland Black Market in Suitings’, Daily Mercury, 28 May 1947, 1.

Minister for Trade and Customs and the Commonwealth Rationing Commission, The Black Market is the Traitor’s Market (Adelaide: K. M. Stevenson, Government Printer, 1943), 1.

‘Theft of Clothing Materials: Believed Intended for Black Market’, Advocate, 30 May 1946, 3.