Sunday Mail (Brisbane), 2 March 1952, 5

'Fashion: Bodgie Styles for Spring', Pix (Sydney), 14 July 1951, 30

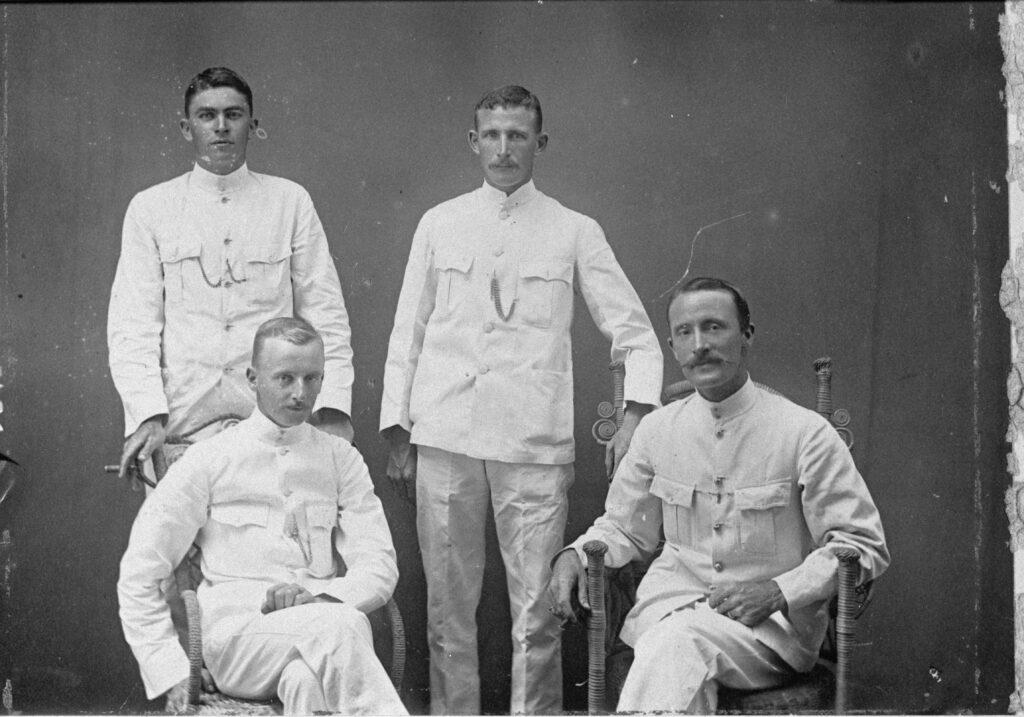

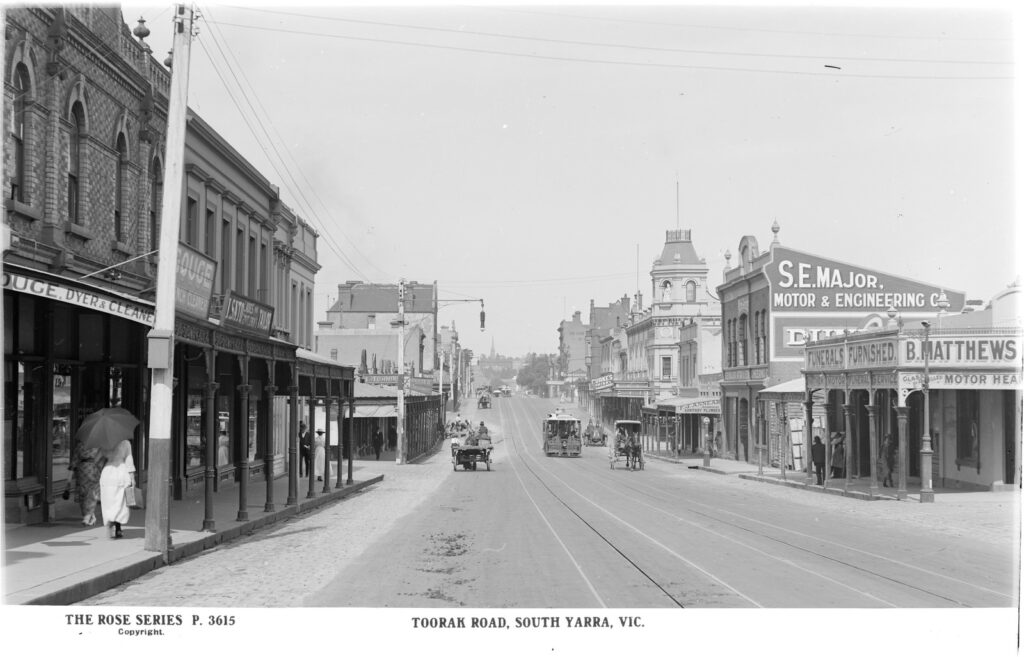

In the decades after Brisbane served as a Pacific base for US troops during World War II, plenty of young rock’n’fans emerged in this northeastern Australian city. Dubbed ‘bodgies’ and ‘widgies’ in the local vernacular, these teens and early-twentysomethings dressed in a style similar to the Teds in Britain.

'Bodgies, Widgies Have Mighty Night—But Def!', Pix (Sydney), 10 March 1951

For the female widgies who frequented Jack Busteeds, a venue in Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley where rock’n’roll fans danced to recorded music, the fashion in the ’50s was a skintight skirt worn with t-shirt and high heels. The other favoured skirt was fuller, with multiple colourful petticoats designed for exposure amid hectic jiving on the dance floor.

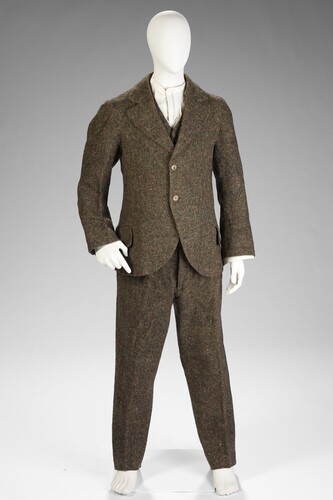

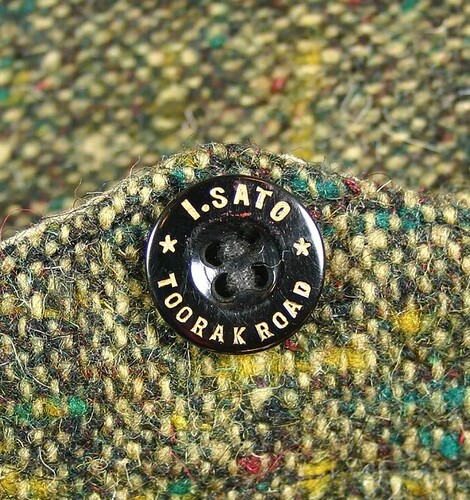

For male bodgies, the sharpest look involved suits with wide-shouldered drape jackets and hair long enough on top to be tousled and Bryl-creamed in the manner of a Tony Curtis or Cornel Wilde. In Brisbane, the most daring and coveted of these suits were custom-made by the tailor, Chris Leon, whose menswear store was close to the Rex Theatre in Fortitude Valley. The jackets had wide shoulders and a padded chest fixed by a single button ‘strategically placed between your navel and your best friend’, as former Brisbane bodgie Des Wallace later recalled.

Wallace detailed his memories of bodgie fashion in 1950s Brisbane in an oral-history interview with the music historian Geoff Walden for his 2003 PhD on Queensland rock’n’roll. Walden interviewed a host of Brisbaneites at the turn of the millennium, and most were remarkable for how well they remembered their favourite bodgie or widgie outfits, sometimes in gorgeous detail. For example:

- The British migrant turned drummer Alan Campbell told Walden of the first pair of trousers he was allowed to wear in Brisbane in 1958; the year he graduated from shorts at the age of sixteen. The trousers were black with green flecks and had very tight cuffs, and he wore them with pointed winkelpicker shoes and an Elvis hairdo. The trousers made him feel ‘great’ and ‘grown up’, Campbell recalled.

- The second-generation Italian migrant Angelo Macaudo remembered spending three-quarters of his wage on his clothes and hair as a teenaged rock-n’roll fan in the 1950s. A good portion of this expense was outlaid at Leon’s menswear store in the Valley. Macuado also recalled the shift in bodgie fashion across the fifties. The fashionable silhouette at first involved pegged trousers (full at the top and knees tapering to tight cuffs at the bottom), but later modulated to stovepipes (narrow all the way down). The favoured look also shifted from colourful fabrics such as the bright yellow and pink curtain materials Leon used for suits earlier in the decade to black suits worn with white t-shirts or black-and-white collared shirts.

- Like Macaudo, Des Wallace remembered spending much of his weekly wage on his clothing. He told Walden that his standard Saturday-night dress in the fifties was a ‘french poplin striped Ivy League-style shirt with a button-down collar’, a drape coat ‘about three inches longer than a traditional sports coat’ and trousers with ‘twenty-six inch knees, two-inch reverse pleats and fourteen-inch bottoms’.

It is probably unlikely that Wallace’s outfit was quite as mannered as the one worn by a model at the top of this post in a magazine-perfect version of Sydney bodgie style in 1951. Yet the extremely precise set of specifications still suggests how much attention Wallace paid to his dress at this time. I am suddenly seized with bodgie/Teddy boys’ fashion longing: could Chris Leon make make me a suit to Wallace’s specs in hot pink curtain material and with a lassoo-style feature hanging from the belt, please?

References

W. Ross Johnston, ‘Bischof, Francis Erich (Frank) (1904-1979)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography (Canberra: Australian National University, 1993).

Oral history interviews conducted by Geoffrey Walden with Des Wallace, Brian Gagen and Betty McQuade in Brisbane Rock’n’Roll in the 1950s – Oral Histories, 1951-1960, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Bill Osberby, ‘Here Come the Teds’, Museum of Youth Culture, n.d., https://www.museumofyouthculture.com/teds/

‘Bodgies, Widgies Have Mighty Night—But Def!’, Pix (Sydney), 10 March 1951

Geoffrey Walden, ‘It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll But I Like It: A History of the Early Days of Rock ‘n’ Roll in Brisbane… As Told by Some of the People Who Were There’, PhD Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, 2003.