Yesterday I had a chat to Libbi Gore on her program, This Weekend Life on ABC Radio Melbourne (from 38:20), about the history of denim jeans. I wrote a short post for this blog on jeans earlier this year, but Libbi, I and a number of lovely callers centred our discussion firstly in the 1850s and then a century later in the 1950s.

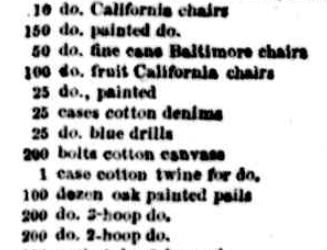

The 1850s has captured my attention as it’s where I’ve been able to find some of the first references to denim cloth being imported into Australia. In 1853, an auction of the cargo of the American Ship Sooloo was advertised in Melbourne’s Argus and Tasmania’s Colonial Times newspapers. Its cargo included 25 cases of ‘cotton denims’.

It’s perhaps not surprising that the Sooloo’s American cargo including denim cloth as, although its earlier origins are found in Europe, it was in nineteenth century America that denim became widely used for sturdy, hard-wearing clothing.

The cotton denim in the 1850s was made into trousers when jeans, as we know them, weren’t patented until 1873 by Levi Strauss and Co (Levi Strauss and his partner, tailor Jacob Davis) in San Francisco. Readymade denim trousers, jackets and overalls were advertised in Australia across the following decades. The focus was on these garments as practical and durable. The heavy-weight cloth was strongly sewn. It was also cheap – denim was, in fact, cheaper than other cloths used for workwear such as drill, ‘mole’ or courduroy.

Around 1950, however, denim shifted from a fabric for workwear to something more fashionable, particularly for Australia’s youths. In this post-war period influenced by American culture, music and style, young men and women alike embraced denim jeans.

This included the bodgies and widgies, an Australian youth subculture that incorporated jeans into its styling. John O’Shea’s article for Melbourne’s Herald newspaper in 1951, titled ‘And they call it music!’, reported in slightly-shocked tones of dance halls and night clubs packed with young people who were ‘mostly in their teens or just out of it’. They jived or jitterbugged to bands playing swing and jazz. They were ‘eccentric in hair style and dress’, some wearing jeans and windcheaters with their hair in the popular Cornel Wilde style (Melissa has written more on this hairstyle for our blog in The Cornel Wilde Boys of North Bondi).

In 1956, the Argus newspaper was more scandalized as it reported a police chase of a stolen new Holden through the now-leafy Melbourne suburb of Brighton. Inside the car, the police found a ‘jeans-and-sweater clad, 16-year-old “widgie”’. The stolen car was driven by her 17-year-old bodgie boy. They were the new face of Melbourne’s crime, the article suggested, with 65% of crime in the city reportedly ‘committed by folk under 21 years’.

While jeans were a ready symbol of youth and rebellion that decade, in those that followed broad swathes of Australians adopted denim whether for comfort, to express their individuality or to be part of a group.

References

Advertising, Argus, 29 July 1853, 8.

Advertising, Colonial Times, 14 July 1853, 3.

Geoff Clancy, ‘Police Beat’, Argus, 20 October 1956, 17.

John O’Shea, ‘And they call it music!’, Herald, 5 May 1951, 9.