Exhibition Review

Along with documenting the Australian Menswear project’s research, one of my aims for this blog is to draw attention to already-existing research on twentieth-century Australian men’s engagement with clothes.

Unlike other places where a thriving corpus of publications on historical men’s fashion exists, the work in Australia is scattered and thin overall. With this in mind, my colleague Lorinda and I will often post about publications, exhibitions and online commentaries on twentieth-century Australian menswear, hoping to make the disparate more centralised.

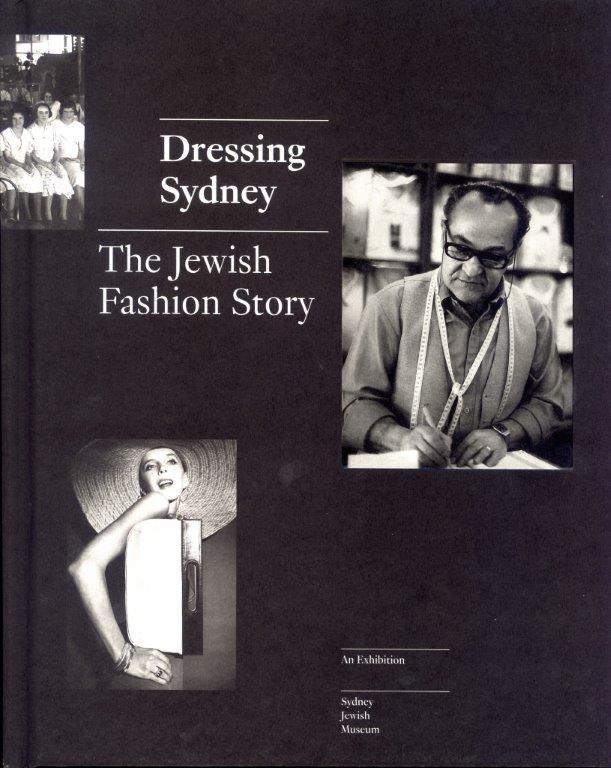

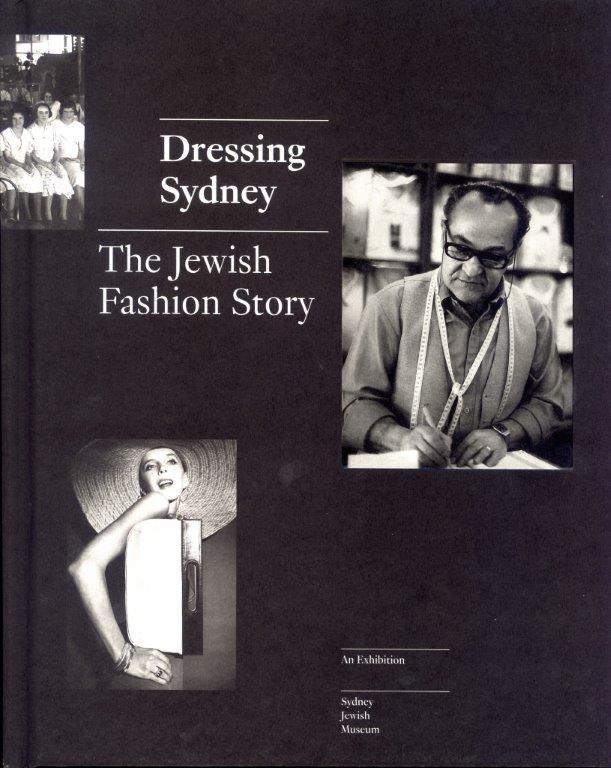

I begin with a mention of the Dressing Sydney exhibition at the Sydney Jewish Museum (January 2013-January 2014). I must also mention the stunning hardcover book accompanying it by curator Robyn Sugarman and fashion historian Peter McNeil.

Dressing Sydney charted the impact of Jewish immigrants and their offspring on Sydney’s rag trade, using garments and photographs gifted or loaned by the families and an extraordinary 150 hours of interviews.

Sydney’s Jewish community – including Holocaust survivors – contributed in heavy number to the local clothing and fashion industries. They did so as workers, designers, owner-managers of factories and the founders of companies that included menswear labels Anthony Squires and Whitmont Shirts.

In some cases, Jewish immigrants drew on expertise developed in Europe when they joined the Australian schmatte (rag) trade. In other cases, they were simply responding to the fact that the industry depended on cheap immigrant and female labour and had no formal qualifications for entry.

Dressing Sydney was not the first foray into the history of Jewish input into the Australian clothing trade. The Australian Jewish Museum produced a comparable exhibition focused on Melbourne in 2001. An entry in the Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion followed; ditto a memoir evocatively called Schmattes: Stories of Fabulous Frocks, Funky Fashion and Flinders Lane.

Dressing Sydney was distinctive, however, due to its rich grounding in oral history and cavalcade of artefacts, images of advertising and fashion shoots, photographs of hawkers, business owners and lovely candid snaps of workers on the factory floor. McNeil’s essay in the catalogue also remains a standout due to its detail about the development of Sydney’s clothing and textile industries.

Having had the fortune to co-edit a special issue of Fashion Theory and convene an international fashion studies symposium with Peter McNeil, I know firsthand his encyclopedic knowledge of fashion history. Given that his Dressing Sydney essay has so much to say about the history of Sydney clothing production, it is excellent that he has made selected pages available via the Open Publications site of his university, UTS. Dressing Sydney is also available for sale from the Sydney Jewish Museum’s online store.

References

Melissa Bellanta and Peter McNeil, eds, Special Issue on Fashion, Embodiment and the ‘Making Turn’, Fashion Theory, 23 (2019). DOI: 10.1080/1362704X.2019.1603856.

Anna Epstein, ‘Jews in the Melbourne Garment Trade’, in Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, vol. 7, Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands, ed. Margaret Maynard (Oxford and New York: Berg, 2010), 95-9.

Anna Epstein, ‘Schmatte Business – Jews in the Garment Trade’ (St Kilda, Melbourne: Jewish Museum of Australia, 20 February-31 May 2001).

Peter McNeil, ‘The Beauty of the Everyday’, in Dressing Sydney: The Jewish Fashion Story, eds. Robyn Sugarman and Peter McNeil (Darlinghurst, Sydney: Sydney Jewish Museum, 2013), 93-157.

Lesley Sharon Rosenthal, Schmatters: Stories of Fabulous Frocks, Funky Fashion and Flinders Lane (South Yarra, Melbourne: self-published, 2005).

Robyn Sugarman and Peter McNeil, Dressing Sydney: The Jewish Fashion Story (Darlinghurst, Sydney: Sydney Jewish Museum, 2013).

Robyn Sugarman, Dressing Sydney – A Behind the Scenes Blog of Curating the Exhibition, accessed 1 August 2019.